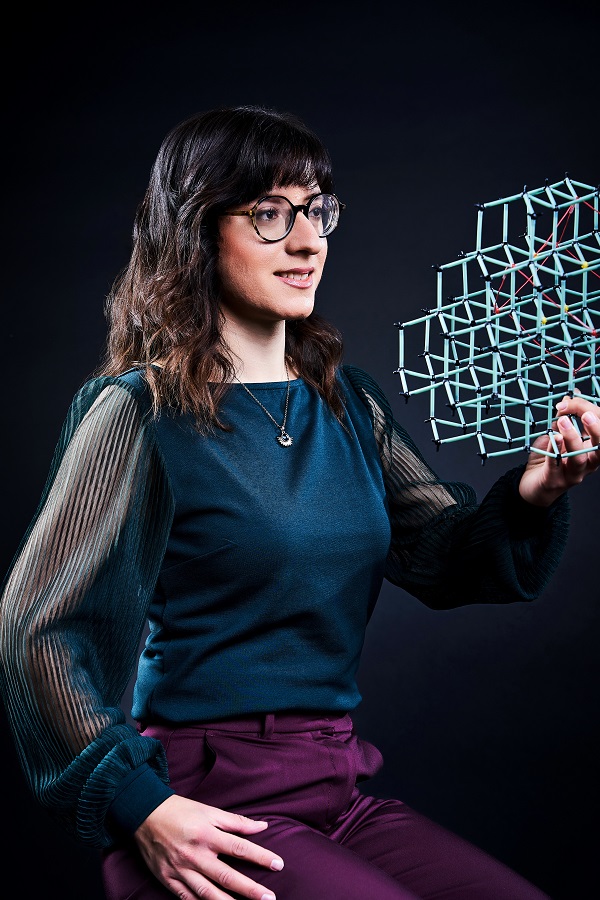

About the Author:

Ida Kaever is studying Liberal Arts and Sciences with a focus on Culture and History at the University of Freiburg.

You could say she has a thing for analysis. Ida likes to spend a day off at the museum or with a book. She has also found a job in the cinema, where there is a lot to interpret (sometimes films, sometimes the guests). And if a fun fact has slipped your mind, Ida may well have saved it – for her ever-growing collection.

“If you change just one parameter, the result looks completely different.”

Jasmin-Clara Bürger, a postdoc since 2023, opens a drawer at the Institute of Microsystems Engineering at the Faculty of Engineering in Freiburg. A box emerges, in which plates, Bürger’s samples, lie neatly sorted next to each other. One of the samples catches the eye, it is green, the top left corner is colored purple, which looks really nice. But this is not about the aesthetic value of any colorful plates. Bürger is currently researching so-called thin-films, i.e. layers of material with a thickness in the nanometer range. This means that the materials Bürger is working with have a size of one billionth of a meter, 10.000 times finer than a human hair. The color of the samples in the laboratory changes depending on the thickness of the thin-film. But what makes these materials so special?

On the nanoscale, materials have completely different properties than they do in their larger state. This process fascinates Bürger. “You can then suddenly turn a completely normal material into a highly functional material that has incredibly great properties for sensors, for example. As fibers, so-called nanowires, these materials can also store a lot of energy and enable a long battery life.”

As soon as the topic of nanowires, the subject of her doctorate, comes up, Bürger seems enthusiastic. She is particularly interested in crystal lattices. In a crystal lattice, the atoms are arranged in a very specific way that repeats like an infinite pattern in all three spatial dimensions. In Bürger’s research, it is essential to investigate and control the crystallinity of materials, as this also influences the behavior of the materials in subsequent components. The nanowires she investigated during her doctorate were monocrystalline and had an almost defect-free crystal lattice.

By choosing the substrate, she was able to influence the crystal orientation and geometry of the nanowires. The choice of substrate is an example of how scientists are able to specifically control the material properties of nanomaterials through precise process control. “If you change just one parameter, the result looks completely different,” says Bürger. It is therefore important to observe closely and understand the processes. For Bürger, this one moment is particularly important: “If I now change this parameter in one direction, then this is what should actually happen, and then you see in the experiment: this is exactly what happens.”

Such findings can ultimately lead to simplifying the lives of many people. For example, the anti-reflective coatings on spectacle lenses are an everyday example of a product of thin film research. Bürger’s current research could ultimately lead to the design of sustainable semiconductor materials for transistors, electrical components. If you listen to Bürger, you can imagine a future in which many things will be made more sustainable. A future in which there are better batteries produced thanks to nanotechnology, in which we are no longer dependent on certain resources that are gradually running out, in short: the world is a different place.

Nanotechnology has already changed Bürger’s own world. Since she has been working with thin-films and nanowires, for example, she perceives orders of magnitude very differently to most people. A micrometer is not necessarily small in her eyes. And when she looks around, she recognizes structures of crystals everywhere. A geometrically shaped table in a café resembles crystals under a microscope. She takes these impressions from everyday life into her research.

Bürger came to the University of Freiburg as a school student. It was the right choice, as she quickly realized that studying microsystems technology suited her, as it is versatile and combines the various STEM subjects. A Bachelor’s degree, a Master’s degree and a doctorate followed. For her, this engendered a great deal of enthusiasm for nanotechnology and working at the university. Here she has the feeling that she can develop freely and research current topics with people who share the same fascination for material science. “There is no longer that one scientist who sits alone in their quiet basement lab and writes down formulas in little daylight,” says Bürger. Nowadays, scientists are engaged in a lively exchange. People meet, discuss current research findings and inspire each other, perhaps only recognizing a potential research gap during the discussion. This happens not only in the laboratory in the working group, but also at conferences or during research stays abroad. Bürger reports enthusiastically about her 6-month stay at MIT in Massachusetts.

However, whether in the US or in Germany, faculties in STEM subjects are generally dominated by men. Even though Bürger does not feel that being a woman working in the male-dominated STEM field has had an impact on her research or her own life, she recognizes that there is an unequal distribution. For example, there are 21 professors teaching at the Institute of Microsystems Technology – and only one female professor.

Perhaps the lack of role models leads to significantly fewer women than men choosing this career path. Nevertheless, they do exist: women are pursuing various careers at the university – including in STEM fields. They work as doctoral candidates, as postdocs, as professors. “That’s why it’s important to make women visible through this campaign,” says Bürger. Especially in basic research in areas such as nanotechnology, there are still so many unknowns to discover and new possibilities to explore, she says. It would be great if more women were to gain a foothold in nanotechnology in the future. The only question that remains is as to what parameters do we need to change in order to achieve this result?